Independent Contractors and Nontraditional Workers: Implications for the Child Support Program

Asaph Glosser and Justin Germain

The Child Support Performance and Incentive Act at 20: Examining Trends in State Performance

Valerie H. Benson and Riley Webster

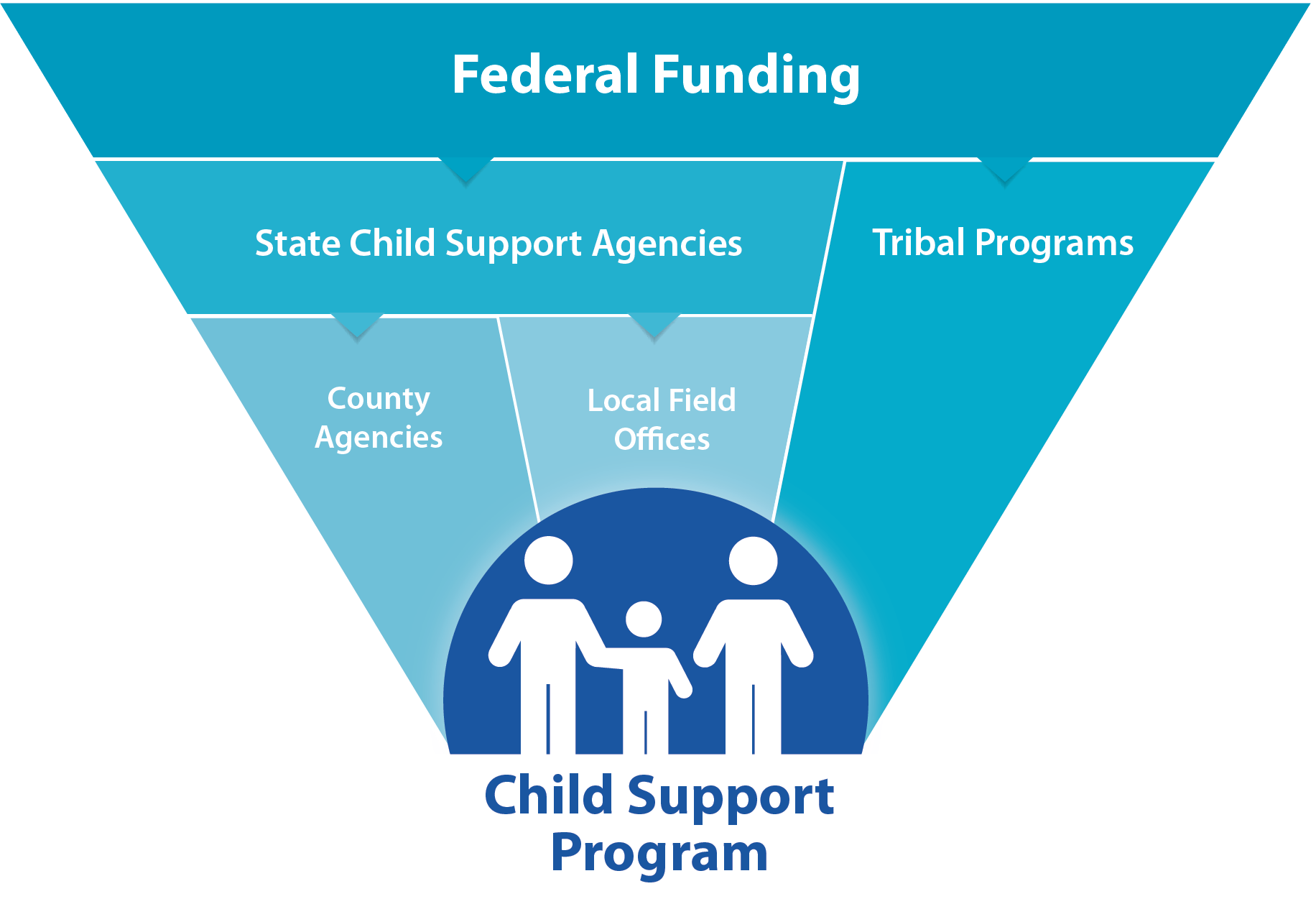

With a culture of continuous improvement, the child support program can use research and analysis to enhance and refine its operation. As a partnership between federal, state, local, and tribal governments, there are opportunities for experimentation at various levels of program coordination and service delivery. Moreover, the substantial data collected by and available to child support agencies provide an opportunity for analyses that improve program operations and inform policy development.

This research agenda is for the broader child support community – federal, state, and local policymakers, program operators, academic researchers and scholars, and program evaluators – to further this spirit of continuous improvement. It identifies potential areas for research and analysis to inform the most pressing policy issues facing the field.

To spark this conversation, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and MEF Associates convened child support practitioners, researchers, and policymakers for the Roundtable for Building the Next Generation of Child Support Policy Research in October 2017. The meeting involved a series of presentations from expert panelists that served as the basis for individual feedback and group discussion. Attendees submitted individual responses about research gaps, engaged in small group discussions with peers, and participated in large group discussions.

The conversations and information collected at the roundtable serve as the foundation for this research agenda.

This agenda highlights eight key issues facing the child support community:

For each issue, the agenda presents ideas and opportunities for future research to be taken up by public, private, and civil society partners. The box below provides a framework for the types of potential research opportunities that could support the issues discussed in this research agenda. They highlight the multiple types of research that can contribute to improvements to child support policy and practice.

This research agenda is not a comprehensive summary of all issues discussed at the meeting, nor a description of every potential area for research. The goal is to identify opportunities for the child support community to build the evidence base and inform continued improvements to the child support program over the next 10 years.

Throughout this document, we classify research ideas and opportunities into several categories, using the following definitions:

Looking for an accessible “audio pairing” to the full Research Agenda? Listen to the Child Support Research Podcast from MEF Presents!

MEF host Justin Germain interviews four child support experts about ways research can inform better child support policy, what they see as the Research Agenda’s most pressing new areas for research in the coming years, and why this matters to the 20+ million children the program serves.

Listen and subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or Stitcher.

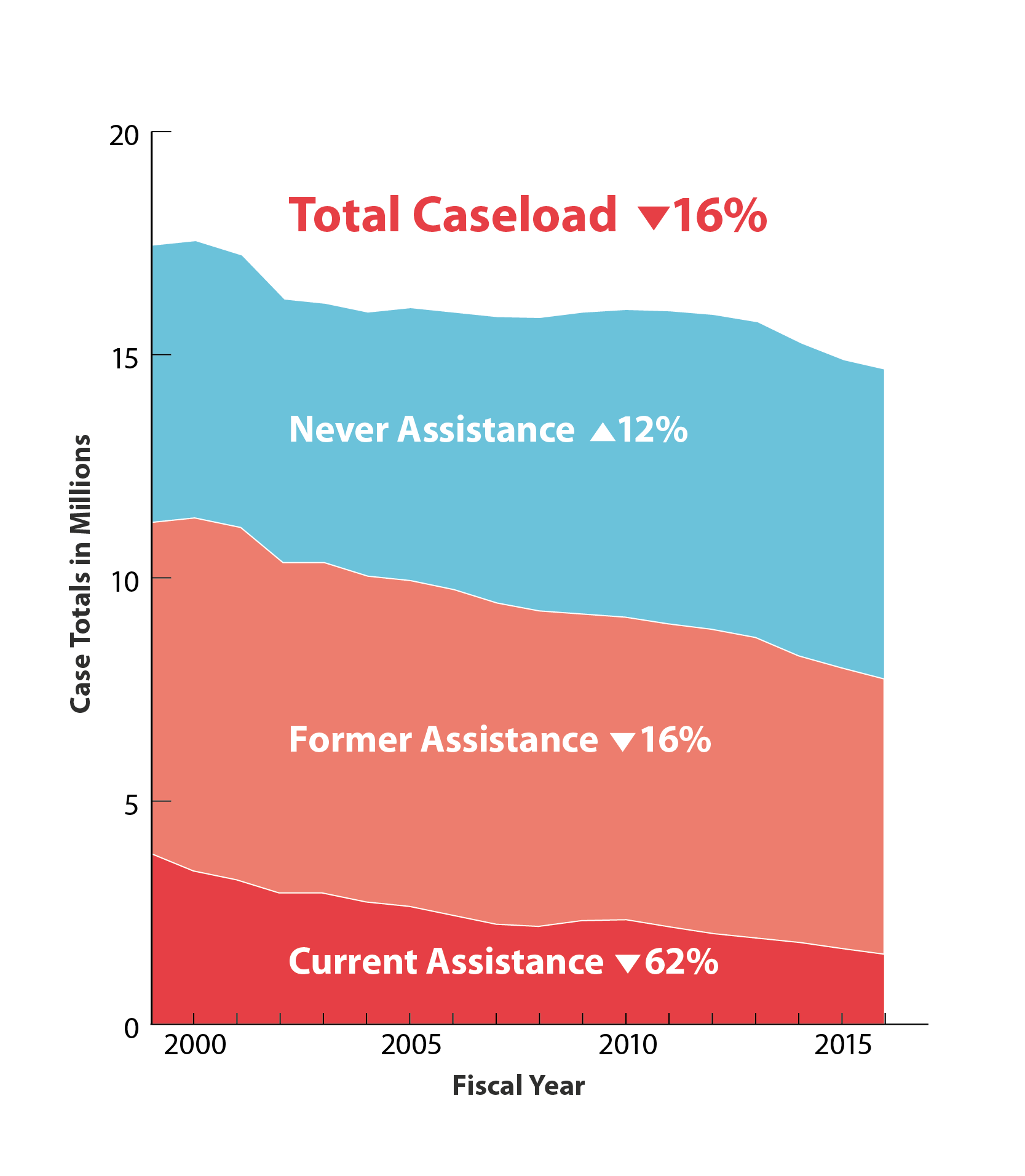

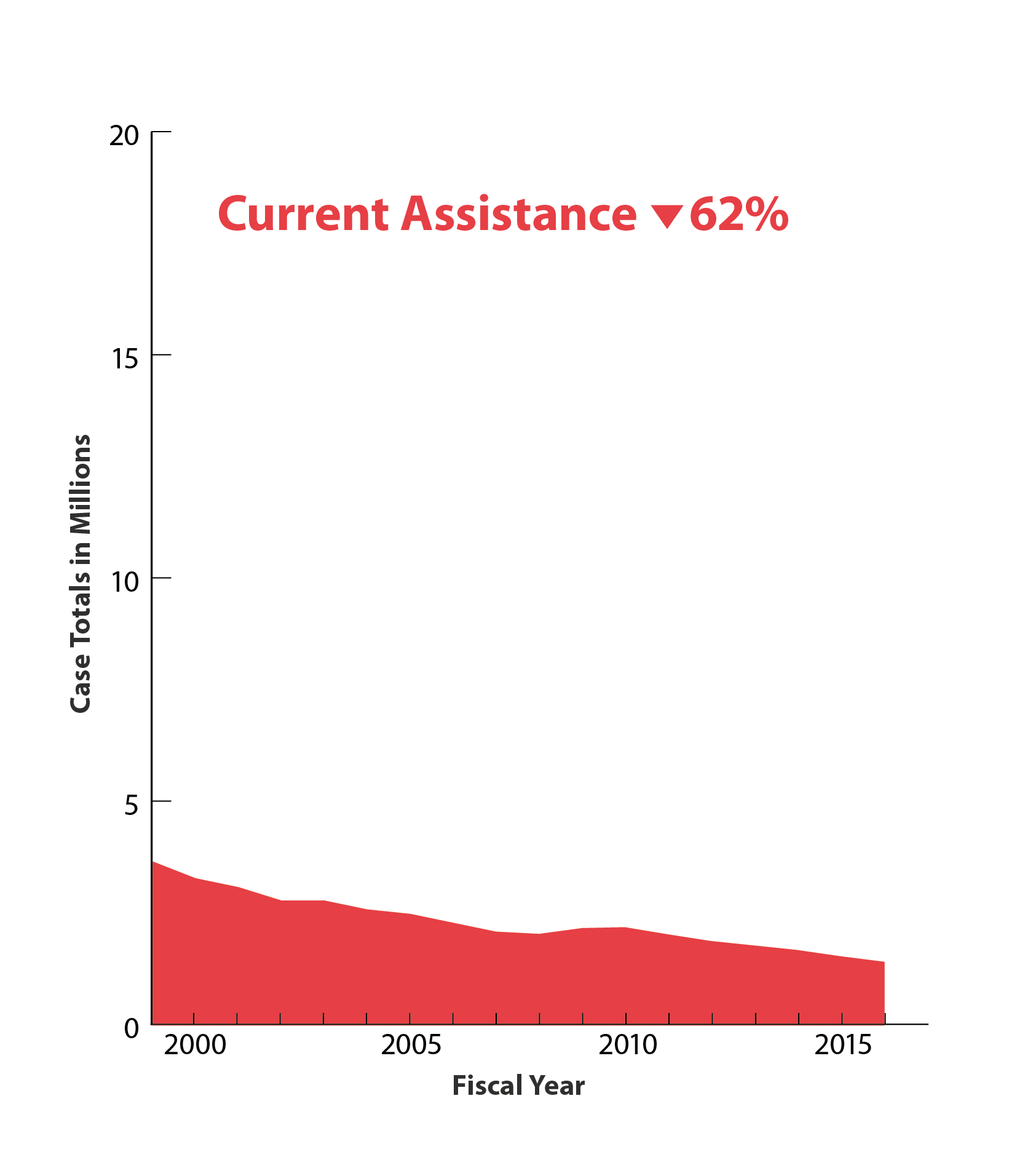

The decline in current assistance cases is most pronounced, driven by the broader reduction in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) caseload following welfare reform. Between 2000 and 2015, the national TANF caseload decreased by over 40 percent, as many states instituted stricter eligibility requirements and shorter time limits for benefit receipt.2

Fewer custodial parents have child support orders. The percent of custodial parents with a child support agreement has decreased from about 60 percent in 2003 to approximately 50 percent in 2015.3 This indicates that there is a large pool of families that could potentially benefit from engaging with the child support program. Though we know that child support caseloads are declining, more information on the characteristics of the remaining caseload and those who are eligible but do not participate in the child support program would allow for programs to better serve their customers.

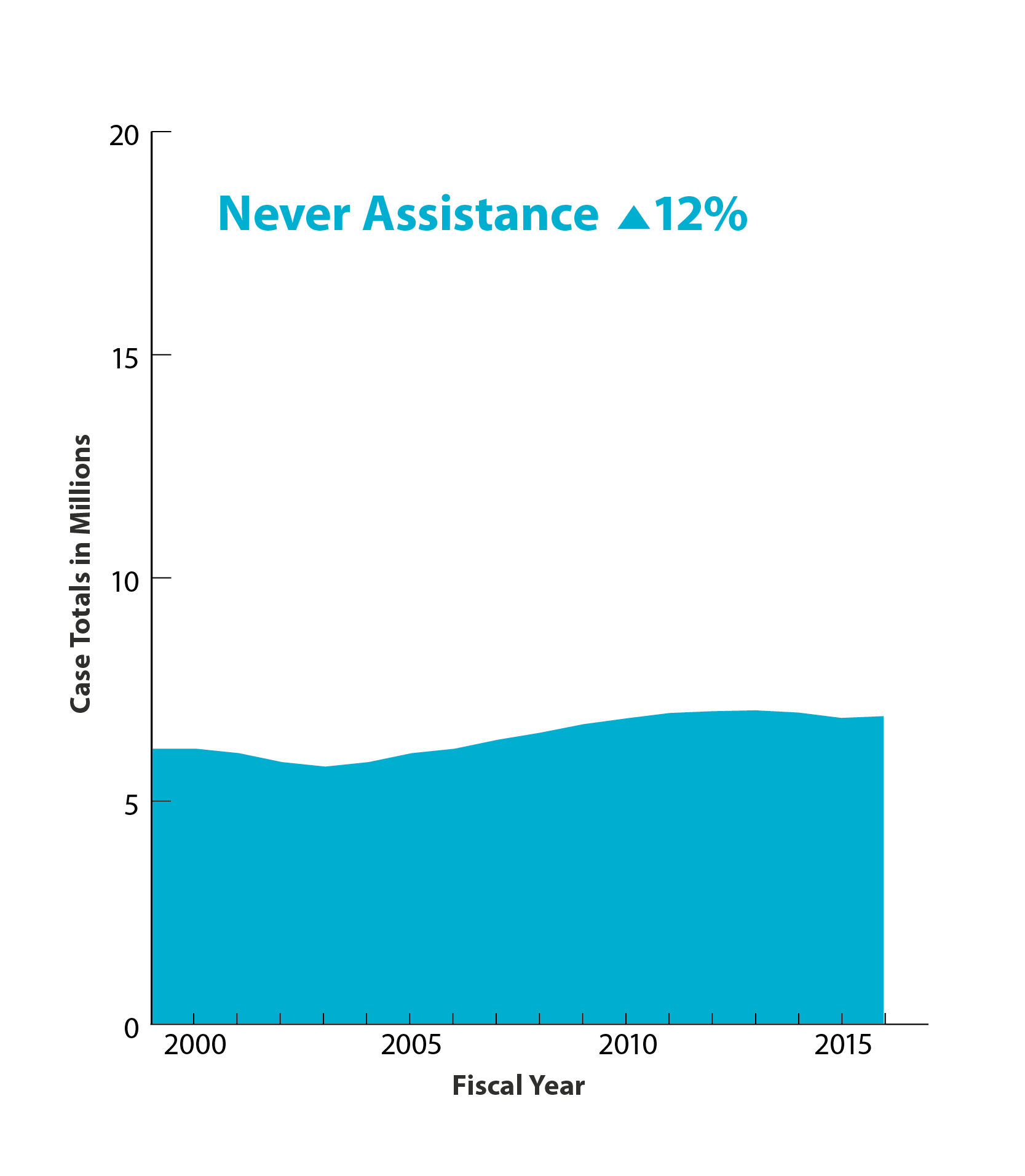

Never Assistance: cases that never received cash assistance from TANF or IV-E foster care maintenance payments.

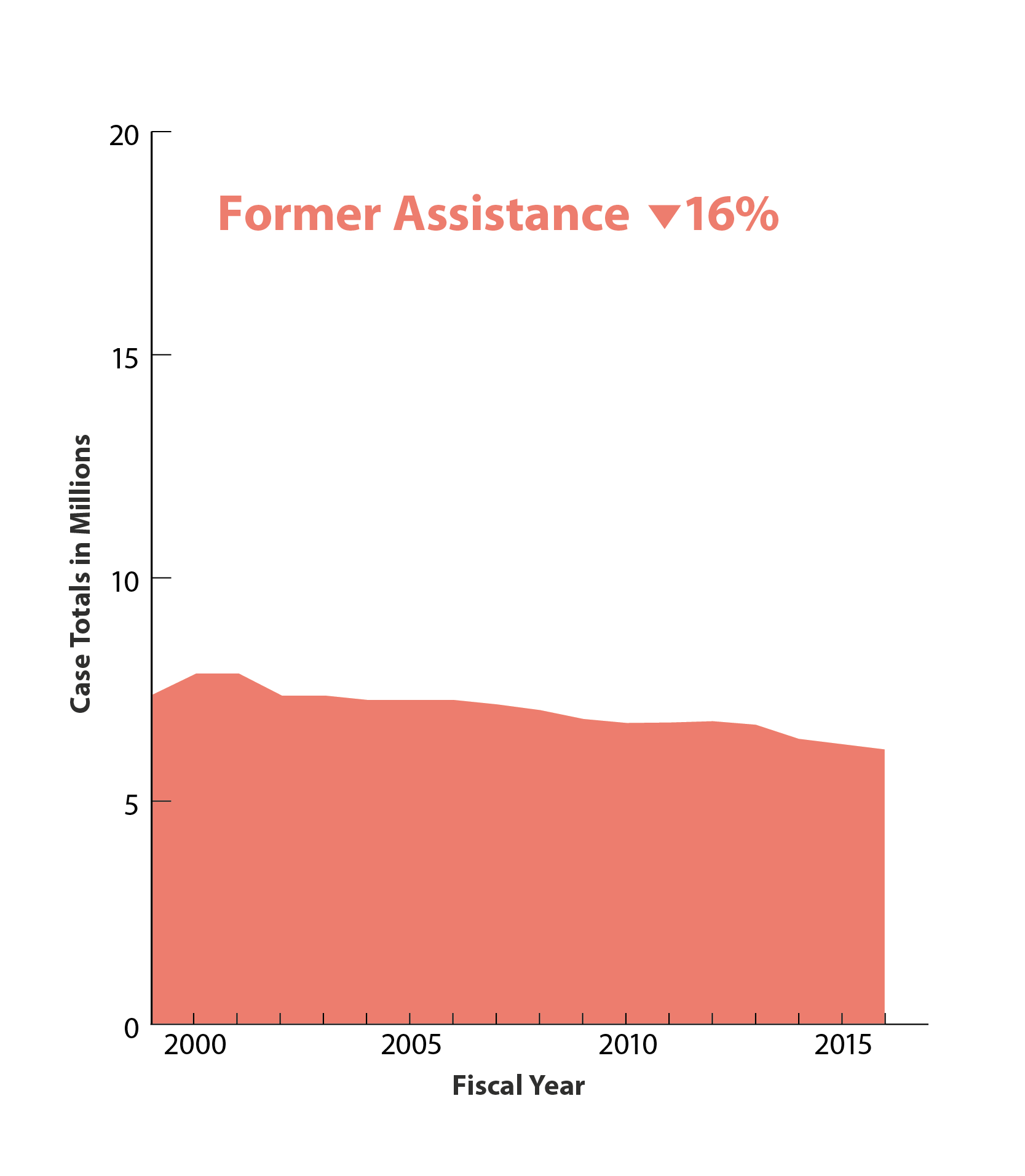

Former Assistance: cases that formerly received cash assistance from TANF or IV-E foster care maintenance payments.

Current Assistance: cases receiving cash assistance from the TANF program or IV-E foster care maintenance payments.

Source: OCSE Form 157, Line 1 + Line 3

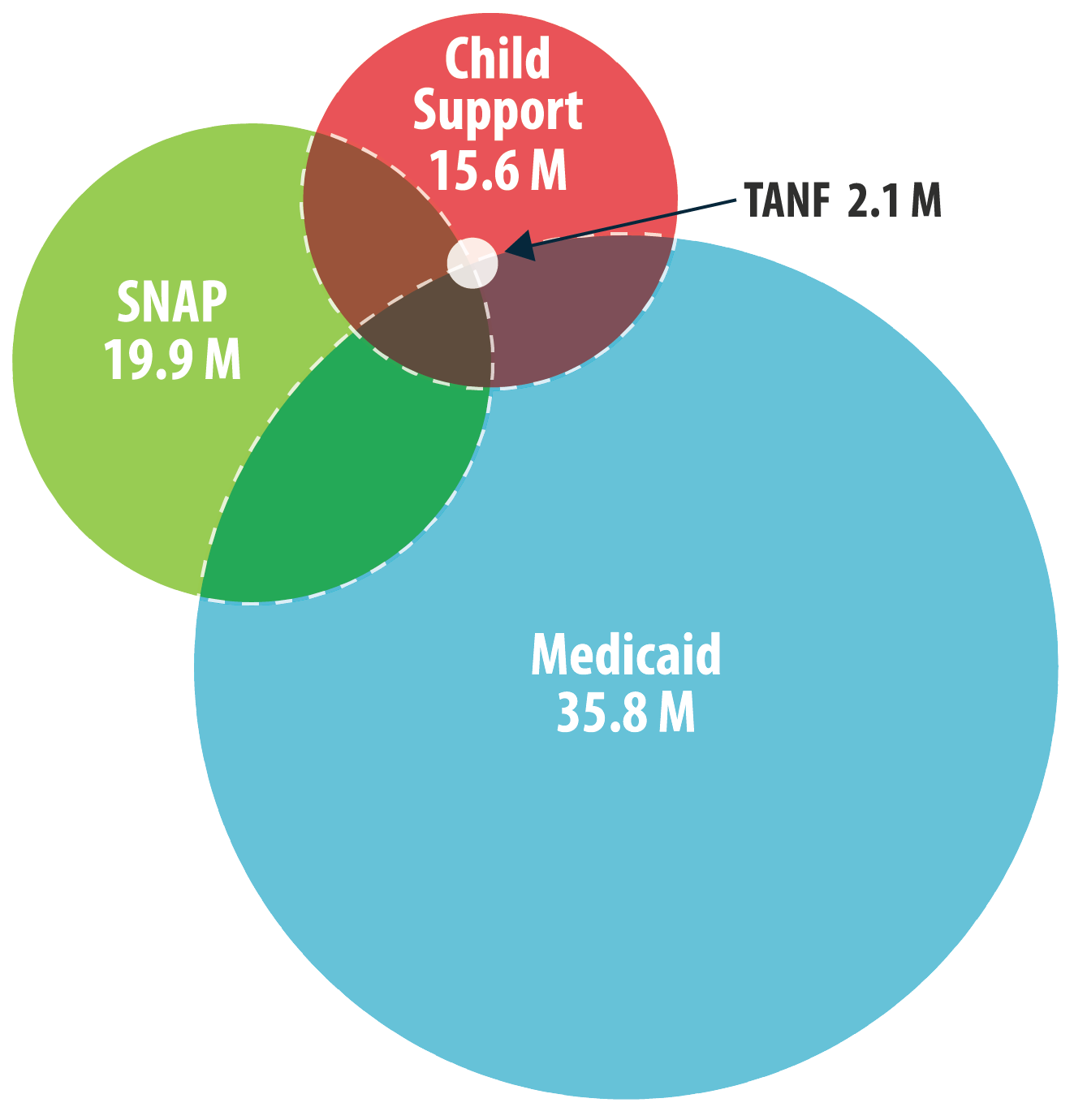

Families receiving TANF are required to participate in the child support program, which includes assigning the rights to their child support to the state while they are receiving benefits. However, smaller TANF caseloads mean that many low-income families are no longer receiving TANF but still receive a range of government benefits such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and subsidized child care.5 For these families, child support may represent an alternative income stream that can augment or replace these benefits. This has the potential to reduce government costs and increase family income.

Fewer linkages exist between the child support program and public benefits programs other than TANF. States have the option to require participation with child support as a condition of receiving SNAP, child care subsidies, and housing assistance, but there is great variation in cooperation policies across the country. Families often have a choice about whether to ask the child support agency to establish a formal support order. More formal referral processes or mandated cooperation between the child support program and other means-tested benefits could result in more families receiving child support services that could benefit from them. However, there is little to no research on the implementation and impact of these policies.6

Families receiving SNAP could increase their family income and reduce government costs by participating in the child support program, though this could raise operating costs of the child support program itself.

Source: OCSE Annual Report

1. What public programs are child support-eligible families and non-custodial parents accessing, and how many have a formal child support order?

2. What would the effects of increased cooperation requirements be on key program outcomes and what would be the costs associated with such requirements?

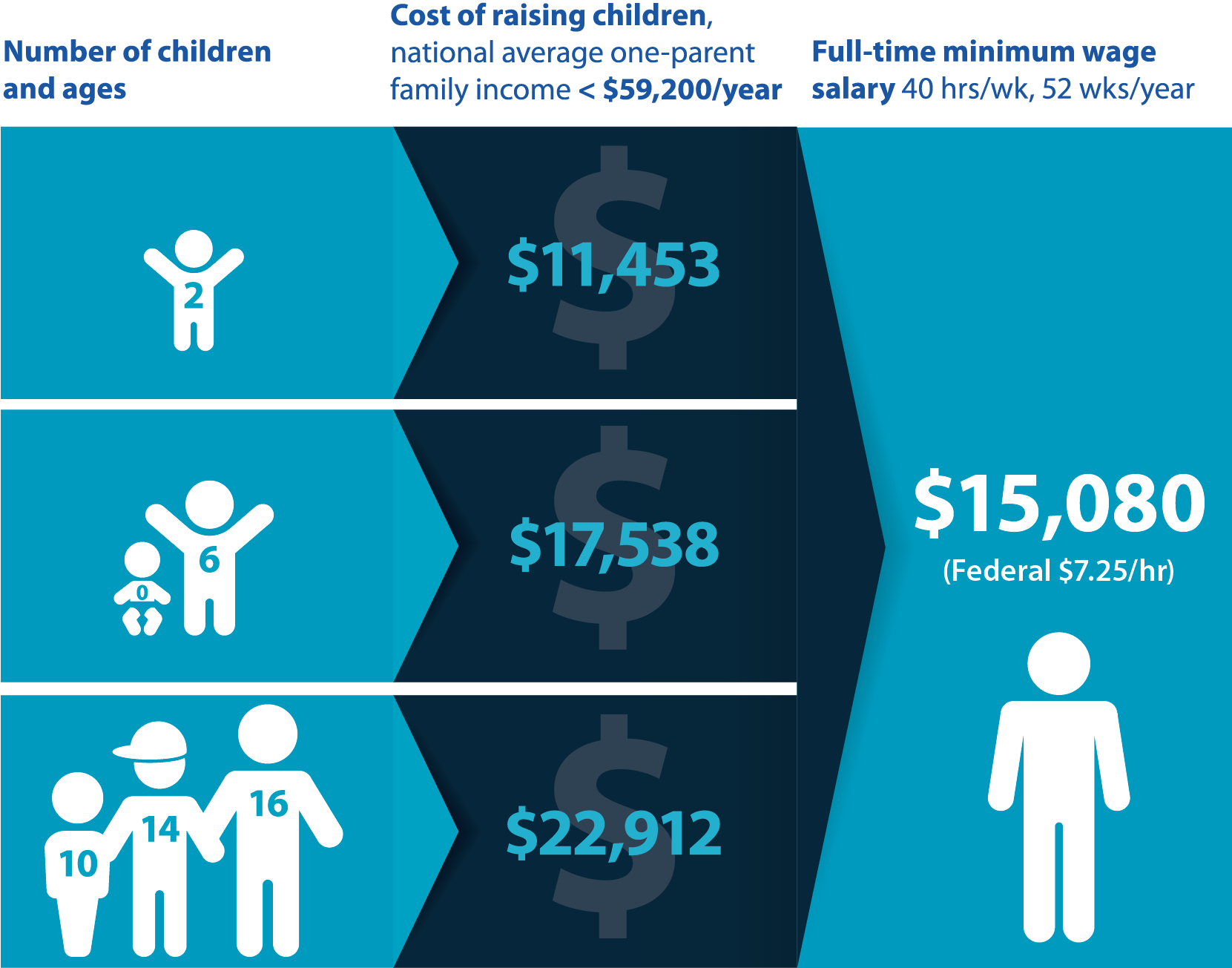

Order establishment processes vary by state, with a mix of procedures used to calculate and determine support obligations based on state guidelines.7 These guidelines consider factors such as one or both parents’ income, number of children, custody arrangement, other child support orders, and medical expenses. The primary goal of the order establishment process is to calculate an order amount that balances the needs of the custodial parent, who is incurring most of the costs of raising a child, while ensuring that the paying parent has enough residual income to cover his or her own basic expenses. States’ approaches to order calculations vary, and the way states apply guidelines can affect order amounts.8 The implementation of the Flexibility, Efficiency, and Modernization rule also has implications for the order establishment process, as it requires a state’s child support guidelines to consider the non-custodial parent’s actual income, and not presumed ability to pay.9

Child support is an important source of income for custodial parents, but most do not receive full payment of their child support order.10 Child support orders define parents’ financial responsibilities toward their children. There is a clear incentive for child support programs to establish orders that provide the necessary funds to cover the costs of raising children while also accurately reflecting parents’ financial circumstances. Orders that are too low may cause added financial stress for low-income custodial parents. Orders that are too high may result in the paying parent having insufficient funds to pay for his or her own basic expenses or accumulating debt due to non-payment. Zero-dollar orders have also become more common in the past two decades; as of 2016, they represented 10 percent of all orders.11 While limited, there is some evidence that setting orders that accurately reflect parents’ ability to pay increases compliance with child support orders.12 Moreover, states receive federal incentive funding based on their ability to collect current support due. Orders that reflect parents’ financial circumstances and ability to pay can also help states increase performance on the federal incentive measures.

1. What approaches to establishing orders help balance the costs of raising children with the financial circumstances of the child’s parents?

2. How does the order amount, relative to parents’ financial circumstances, influence payment behavior?

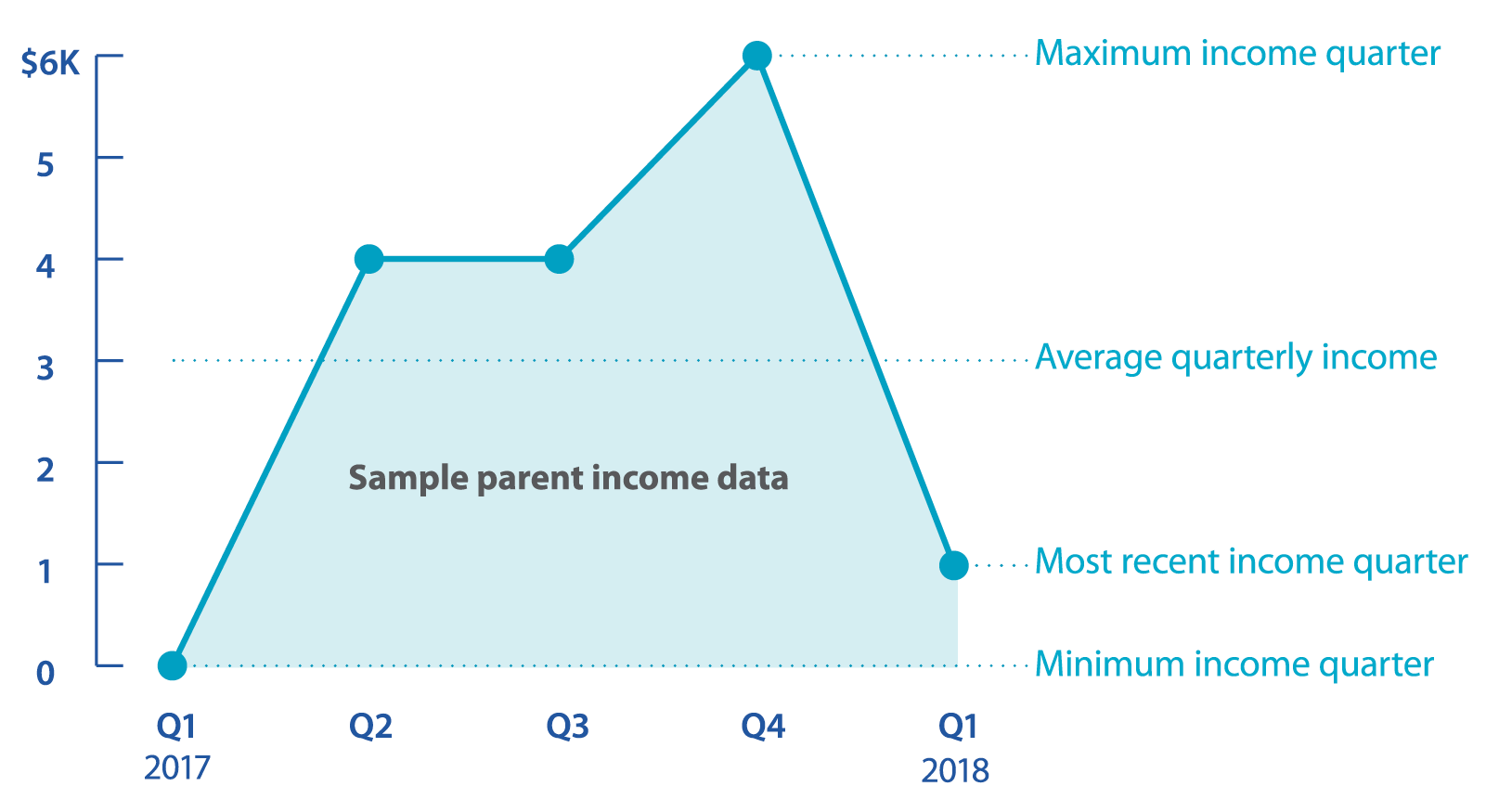

However, low-income populations often have unstable incomes and employment arrangements.13 This instability or lack of earnings negatively affects parents’ ability to meet monthly child support obligations. Even when there is some evidence of prior earnings in quarterly wage data, staff must decide how to interpret inconsistent wages. For example, they can either take the average of earnings from multiple quarters, the highest amount from a given quarter, or some other adjustment based on information obtained through a conversation with one or both parents. In each case, the decision staff make has implications for the order amount. Moreover, child support programs often have limited information, resulting in orders being based on income imputation.14 Yet for most non-custodial parents undergoing imputation, orders often end up being either too high or too low.15

The fluctuations in non-custodial parent income and changes in employment status make it difficult for child support agencies to ensure that orders accurately reflect parents’ financial situations and that custodial parents receive the support they need to pay the ongoing costs of raising a child. The inability to easily assess a parent’s financial profile puts child support programs in a difficult situation. Federal code requires states to establish child support orders within 90 days of paternity establishment.16 For cases in which there is little information on parents’ financial circumstances (or the parents are less responsive to requests for this information), states are left with the choice of either delaying order establishment in the hopes of receiving better information or establishing an order with less complete information. How states handle these situations has implications for both the speed with which orders are established as well as the degree to which the orders accurately reflect parents’ financial circumstances.

At order establishment, parents provide information on recent income. When their income information is incomplete or earnings are inconsistent, there are various ways to calculate income to set an order amount.

1. How can child support programs increase the accuracy of orders for low-income parents while not dramatically increasing time or costs associated with the order establishment process?

The child support program interacts with both parents. These interactions are influenced by the relationship between the parents, informal care and payment arrangements that may be outside the formal program, and legal agreements on access, visitation, and parenting time. Parents’ willingness to contribute financially can be influenced by their feelings related to access, visitation, and the co-parenting dynamic, and custodial parents’ decisions on gatekeeping may also be tied to the non-custodial parent’s provision of formal or informal financial support.19 Moreover, these co-parenting relationships may also be influenced by the parents’ perception of, or experience with, the formal child support program.

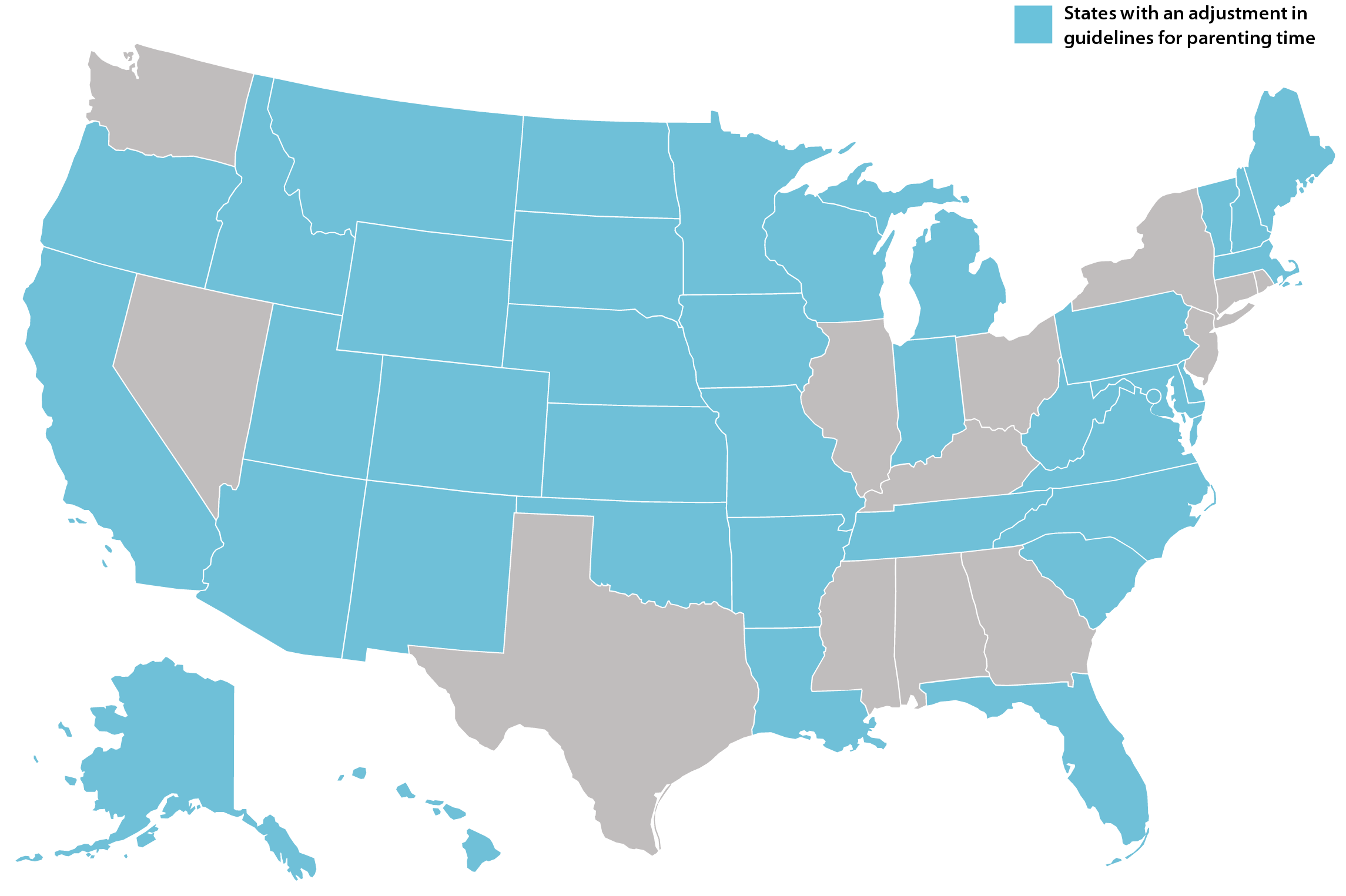

While the child support program has a clear role in facilitating the financial support of children and custodial families, the program’s role in other aspects of the co-parenting relationship is less clear. Thirty-six states consider time spent with the child in the child support guideline calculation that determines the order amount.20 Six states set parenting time orders at the time of the child support order establishment.21 In addition, child support programs can play a role in supporting co-parenting relationships through family strengthening and fatherhood programming. A few states have statewide fatherhood initiatives that formalize these partnerships, whereas other jurisdictions give referrals to community-based services.

Source: McCann, Meghan. Email correspondence with authors (2018). National Conference of State Legislatures.

1. What is the role of the child support program in facilitating co-parenting arrangements or relationships?

2. How do formalized parenting time orders affect compliance with the child support program?

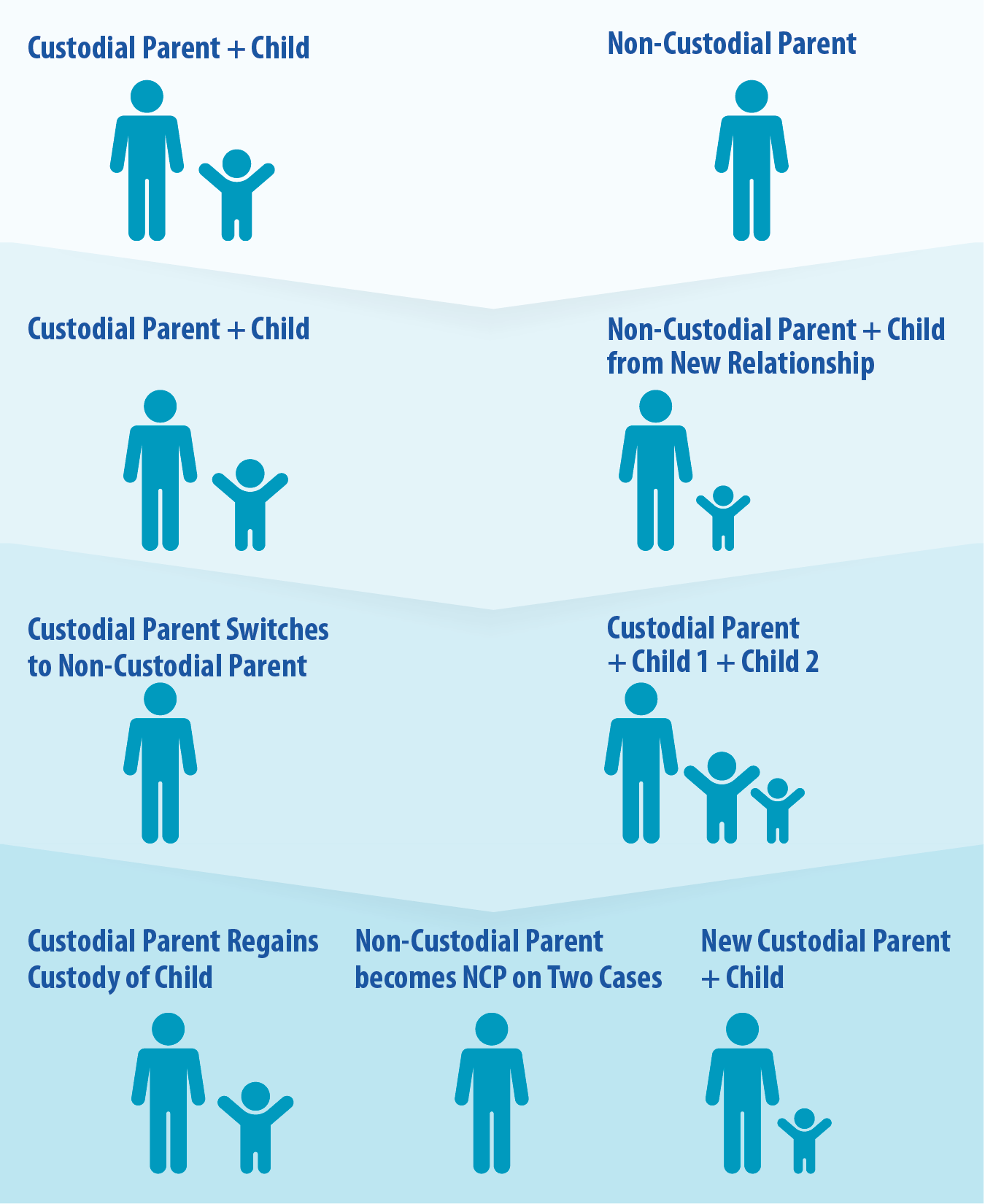

Whether it is changes in employment status, adjustments in which parent is paying child care costs, or shifts in custody arrangements, families’ circumstances change over time. Parents in the child support program are legally entitled to a review of their order every three years that can account for these changes. They can also request modifications to these orders more frequently if there have been more substantial changes.

Child support agencies have access to a large amount of data, but many times agencies are unable to use these data to their full potential due to aging data systems and limited resources for improvements. Child support programs often struggle to track changes in family circumstances and adjust their enforcement approaches based on these changes. Many child support data systems are older and there are limitations on resources available for improvements, so state and local agencies must find creative ways to work within system constraints to serve families.

Child support agencies face challenges in efforts to work in conjunction with families to modify child support orders to reflect current family circumstances. The process for order review and modification is often complicated and time consuming and many parents are not even aware of the option. Low-income parents tend to have less stable employment situations which could impact their ability to pay child support consistently. Family relationships can be complicated, and changing custody arrangements can create confusion about the child support responsibilities of parents and the process for adjusting the child support order.22 Furthermore, parents may be unfamiliar with what are often complicated and at times judicial procedures required to modify support orders.

Child support agencies strive to establish orders that reflect family circumstances and to process requests for modifications to these orders when situations change. Downward modifications due to changes in earnings, job loss, or incarceration can help prevent accumulation of potentially unpayable debt. Upward modifications due to increased earnings can help provide more support to custodial parents and children. However, even when they are potentially eligible, parents often do not apply for modifications to their support orders. Recent tests of attempts to increase requests for modifications among incarcerated parents showed that it was possible to increase the number of parents making the requests. Despite the improvements, the number of parents targeted by these interventions who made requests for modifications remained small.23

1. What technology and systems interoperability would enhance the child support program’s responsiveness to changing family circumstances?

2. Can more timely modifications to child support orders increase payments to families and decrease debt accumulation?

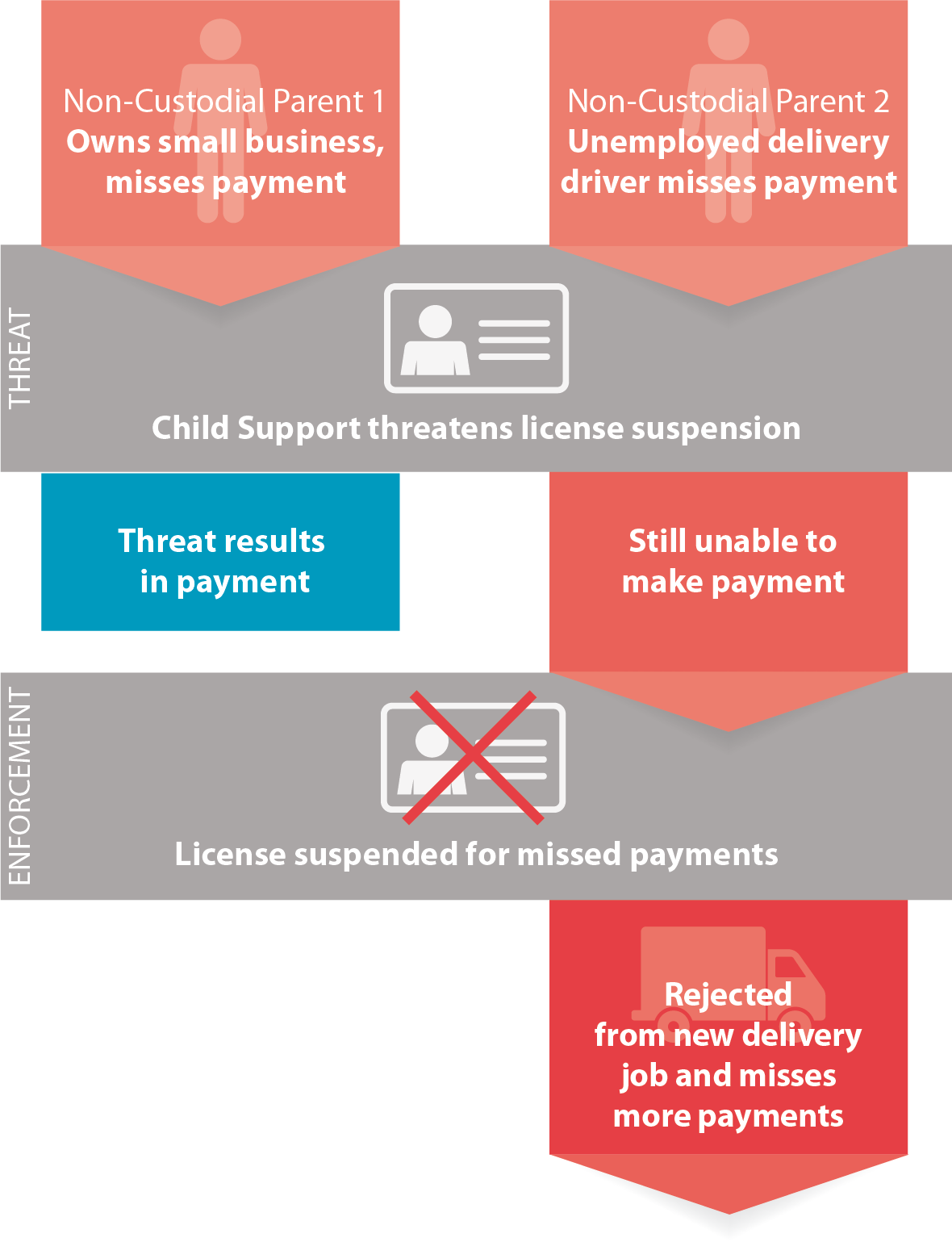

State child support agencies have flexibility in how they apply these tools to enforce orders, and the decisions regarding how these tools are used may be left to the discretion of line staff or determined by the courts. Thus, there is the potential for substantial variation in their implementation, even within a given program. This discretion is often not informed by solid evidence regarding the effect of these tools on cases with different characteristics.

Despite the widespread use of enforcement tools, there is less known about how states and localities use these different tools and what effect they have on compliance. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the effect of these tools differs based on case characteristics such as order amount, receipt of other public benefits programs, or number of child support cases. While enforcement measures may often result in increased compliance, they also run the risk of reducing a parent’s ability to pay child support. For example, for some parents the threat of having their license suspended is the motivation needed for them to make the required payment. For other parents, the loss of a driver’s license might make it that much harder for them to find or maintain a job that will allow them to meet their child support obligation.

Recent investments in predictive analytics and advanced modeling by states and counties reflect a growing interest in understanding the differential effect that these enforcement tools can have on compliance. These efforts include case stratification and using specialized units to enforce orders with certain case characteristics.24 However, interest in the topic has not typically been accompanied by research exploring the effectiveness of these approaches. Research to better understand what enforcement tools are most effective for which families, and at what point in the process, would help programs target resources toward cases which are most likely to benefit.

1. How do state, county, local, and tribal programs use enforcement tools?

2. How well do existing efforts to use data analytics and predictive models work in optimizing the use of enforcement tools?

3. What enforcement tools are most effective for which families, and at what point in the enforcement process?

Given that roughly 80 percent of non-custodial parents are men, this decline in employment has substantial implications for the ability of non-custodial parents to meet their child support obligations. Census survey data reinforce this, with roughly one-third of custodial parents reporting that they have no legal child support agreement established because the other parent could not afford to pay.26 Absent steady income, few non-custodial parents are able to make the child support payments that are critical to support the costs of raising a child.

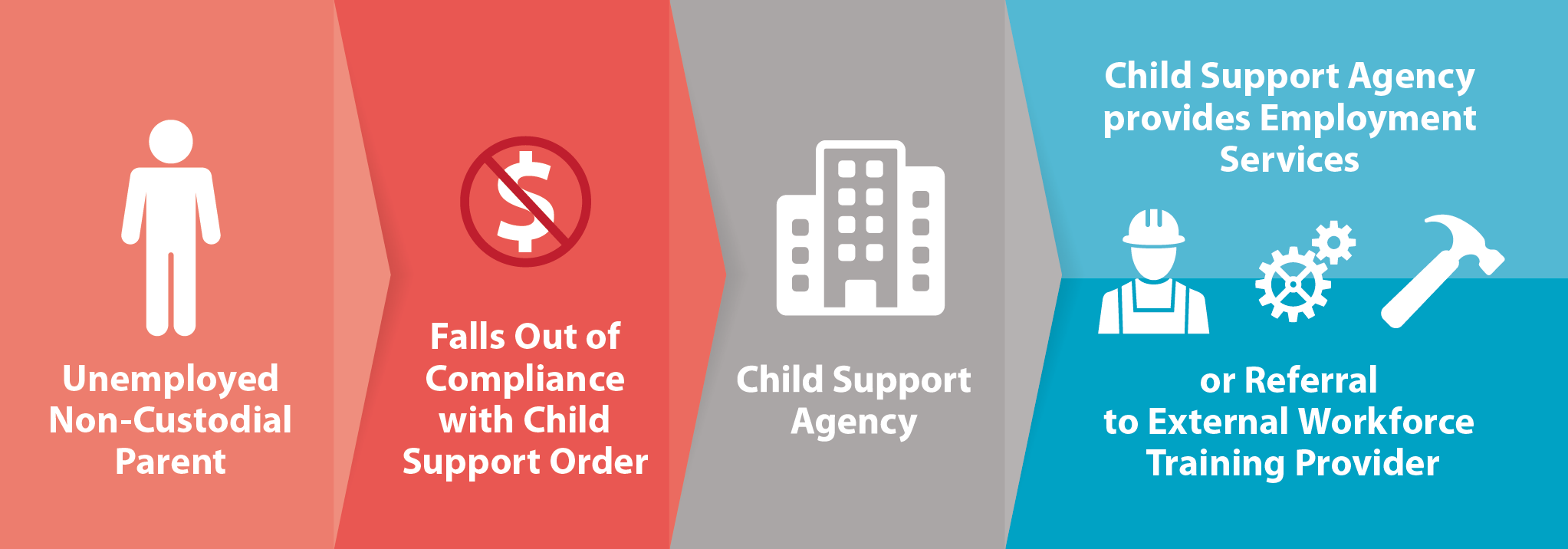

The child support program has not historically played a role in providing employment services for non-custodial parents even though un- or under-employment can be a significant barrier to paying child support. However, child support programs can encourage non-custodial parents to participate in workforce programs designed to increase employment and income. In recent years, some child support agencies have begun to address this barrier by offering employment supports.27 This includes instances where participation in these programs is mandatory and others in which participation in such programs is voluntary.28 Additionally, recent policy guidance from the federal Office of Child Support Enforcement has reinforced that state child support agencies can obtain exemptions that allow them to use their federal incentive funds to fund employment programs.29 Forthcoming evaluation results from the National Child Support Parent Employment Demonstration, funded by the federal Office of Child Support Enforcement, will provide an opportunity for additional learning and potential replication studies.30

While some non-custodial parents evade payment of formal child support, there are others whose low earnings impede their ability to pay. Unstable employment arrangements of low-income populations also have consequences for the stability of child support payments. Many low-income, non-custodial parents are employed in the underground economy, work as independent contractors, or switch jobs frequently.31 Understanding how the child support program can best use employment services to support non-custodial parents and increase earnings stability is a critical step for increasing child support collections.

1. How does child support involvement in the provision of employment services affect child support outcomes, such as payment?

2. How can the child support program collaborate with the workforce system and other agencies providing employment services to better serve customers?

Document how child support agencies engage with employment services and foster partnerships that go beyond referrals to workforce agencies:

Case studies describing:

This agenda presents multiple opportunities for research that can inform the policies and operations of child support programs. It is not exhaustive. Child support often sits at the nexus of complex family relationships and multiple public benefits programs. There are a multitude of factors that influence parents’ ability to meet their child support obligations outside the control of the child support program, such as the broader economy, public health trends like the current opioid epidemic, or the increase in multi-partner fertility. However, the research and analysis ideas described in this agenda can serve as a starting point to help child support programs and research funders use the large amounts of data at their disposal to promote innovation and improvement in policy and operations.

1 Office of Child Support Enforcement (2018). 2016 Child Support Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

2 Administration for Children and Family: Archives (2004). TANF Caseload Data 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Family Assistance (2016). TANF Caseload Data 2015. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Service; Loprest, Pamela J. (2012). How Has the TANF Caseload Changed over Time? Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

3 Grall, Timothy (2018). Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2015. Current Population Reports P60–262. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

4 Anzelone, Caitlin, Jonathan Timm, and Yana Kusayeva (2018). Dates and Deadlines: Behavioral Strategies to Increase Engagement in Child Support. MDRC; Farrell, Mary, Caitlin Anzelone, Dan Cullinan, and Jessica Wille (2014). Taking the First Step: Using Behavioral Economics to Help Incarcerated Parents Apply for Child Support Order Modifications. OPRE Report 2014-37. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Glosser, Asaph, Dan Cullinan, and Emmi Obara (2016). Simplify, Notify, Modify: Using Behavioral Insights to Increase Incarcerated Parents’ Requests for Child Support Modifications. OPRE Report 2016-43. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

5 Parents must cooperate with the child support program to receive TANF, Medicaid, and foster care maintenance payments under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act. States may require individuals receiving other means-tested programs to cooperate with the child support program as well, which has led to variation in which states have cooperation requirements. For more information, see Antelo, Lauren and Erica Meade (2018). How Many Families Might be Newly Reached by Child Support Cooperation Requirements in SNAP and Subsidized Child Care, and What are their Characteristics? Washington, DC:Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

6 A 2014 study explored potential effects in Utah of required participation in the child support program among SNAP recipients. Hopkins, Rodney W. and Robbi N. Poulson (2014). Food Stamp Child Support Cooperation Study. Salt Lake City, UT: Social Research Institute, University of Utah.

7 Gardiner, Karen N., John Taponga, and Michael E. Fishman (2002). Administrative and Judicial Processes for Establishing Child Support Orders. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Support Enforcement.

8 Venohr, Jane C. (2013). Child Support Guidelines and Guidelines Reviews: State Differences and Common Issues. Family Law Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 3, p. 327–352.

9 Antelo, Lauren and Erica Meade (2018). How Many Families Might be Newly Reached by Child Support Cooperation Requirements in SNAP and Subsidized Child Care, and What are their Characteristics?. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

10 Renwick, Trudi and Liana Fox (2016). The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2015. Current Population Reports P60–258. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Grall, Timothy (2018). Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2015. Current Population Reports P60–262. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

11 Sorensen, Elaine (2018). Exploring Trends in the Percent of Orders for Zero Dollars. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Support Enforcement.

12 Takayesu, Mark (2011). How Do Child Support Order Amounts Affect Payments and Compliance? Santa Ana, CA: Orange County Department of Child Support Services.

13 Morduch, Jonathan and Rachel Schneider (2013). Spikes and Dips: How Income Uncertainty Affects Households. U.S. Financial Diaries.

14 Fleming, James C. (2017). Imputed Income and Default Practices: The State Directors’ Survey of State Practices Prior to the 2016 Final Rule. McLean, VA: National Child Support Enforcement Association.

15 Plotnick, Robert D. and Alec I. Kennedy (2018). How accurate are imputed child support orders? Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 88, p.490–496.

16 45 CFR § 302.56.

17 Pearson, Jessica (2015). Establishing Parenting Time in Child Support Cases: New Opportunities and Challenges. Family Court Review, Vol. 53, Issue 2.

18 Grall, Timothy S. (2011). Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau Economics and Statistics Administration.

19 Dubey, Sumati N. (1995). A Study of Reasons for Non-Payment of Child Support by Non-Custodial Parents. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, Vol. 22, Issue 4 December, Article 8; Nepomnyaschy, Lenna (2007). Child Support and Father-Child Contact: Testing Reciprocal Pathways. Demography: Vol. 44, No. 1, February 2007, p. 92–112; Turner, Kimberly J. and Maureen Waller (2016). Indebted Relationships: Child Support Arrears and Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement With Children. Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 79, No. 1, February 2017, p. 24–43.

20 McCann, Meghan. Email correspondence with authors (2018). Denver, CO: National Conference of State Legislatures.

21 Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Support Enforcement.

22 Cancian, Maria and Daniel R. Meyer (2011). Who Owes What to Whom? Child Support Policy Given Multiple-Partner Fertility. Social Service Review, Vol. 85, No. 4, p. 587–617.

23 Farrell, Mary, Caitlin Anzelone, Dan Cullinan, and Jessica Wille (2014). Taking the First Step: Using Behavioral Economics to Help Incarcerated Parents Apply for Child Support Order Modifications. OPRE Report 2014-37. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Glosser, Asaph, Dan Cullinan, and Emmi Obara (2016). Simplify, Notify, Modify: Using Behavioral Insights to Increase Incarcerated Parents’ Requests for Child Support Modification. OPRE Report 2016-43. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

24 Plotnick, Robert, Asaph Glosser, M. Kathleen Moore, and Emmi Obara (2015). Increasing child support collections from the hard-to-collect: Experimental evidence from Washington State. Social Service Review, Vol. 89, No. 3; Logan, Leticia, Correne Saunders, and Catherine E. Born (2011). Maryland Child Support Case Stratification Pilot: November 2010-April 2011. Baltimore, MD: University of Maryland School of Social Work; Bean, Margot, Kevin Bingham, John White, and James Guszcza (2011). Advanced analytics for child support programs: From reactive enforcement to proactive prevention—Part II. Deloitte; Formoso, Carl and Qinghua Liu (2010). Arrears Stratification in Washington State: Developing Operational Protocols in a Data Mining Environment. Washington State Department of Social and Health Services Economic Service Administration Management Accountability & Performance Statistics Office.

25 Executive Office of the President (2016). The Long-Term Decline in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President Council of Economic Advisors.

26 Grall, Timothy (2018). Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2015. Current Population Reports P60–262. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

27 Work-Oriented Programs for Noncustodial Parents: Program Innovation Maps (2014). Washington, DC: Office of Child Support Enforcement, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

28 Schroeder, Daniel and Nicholas Doughty (2009). Texas Non-Custodial Parent Choices: Program Impact Analysis. Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin Ray Marshall Center; Paulsell, Diane, Jennifer L. Noyes, Rebekah Selekman, Lisa Klein Vogel, Samina Sattar, and Benjamin Nerad (2015). Helping Noncustodial Parents Support Their Children: Early Implementation Findings from the CSPED Evaluation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Support Enforcement; Couch, Kenneth A., Elaine Sorensen, and Larry Mead (2010). “Point/Counterpoint.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Vol.29, No.3, 603–620.

29 Lekan, Scott M. (2018). Information Memorandum: Use of IV-D Incentive Funds for NCP Work Activities. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Support Enforcement.

30 The most recent findings from this demonstration can be found at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/grants/grant-updates-results/csped

31 Miller, Daniel P. and Ronald B. Mincy (2012). Falling Further Behind? Child Support Arrears and Fathers’ Labor Force Participation. Social Service Review, Vol. 86, No. 4, p. 604–635.

We are grateful for the strong collaborative spirit of our Project Officer, Lauren Antelo. She has been a valued partner throughout this project. At ASPE we also thank Jennifer Burnszynski and Kelly Kinnison. We also thank staff at the federal Office of Child Support Enforcement for their thoughtful comments on this document. At MEF, Mike Fishman provided helpful comments on drafts throughout this process.

Our collaborators at Blank Space, Mindi and Riley Raker, expertly designed this website and the accompanying document. We value their creativity, flexibility, and keen design eye.

Finally, this work was deeply informed by child support practitioners, researchers, and policymakers who attended the October 2017 Roundtable for Building the Next Generation of Child Support Policy Research. While this research agenda is not meant to reflect the opinions of these attendees, we are extremely appreciative of their intellectual engagement and spirited discussion during the roundtable.

Independent Contractors and Nontraditional Workers: Implications for the Child Support Program

Independent Contractors and Nontraditional Workers: Implications for the Child Support Program

Asaph Glosser and Justin Germain

The Child Support Performance and Incentive Act at 20: Examining Trends in State Performance

The Child Support Performance and Incentive Act at 20: Examining Trends in State Performance

Valerie H. Benson and Riley Webster